FEATURE (Part One): Ukraine: Attempting to Escape Russia's Grasp (A Geopolitical Analysis)

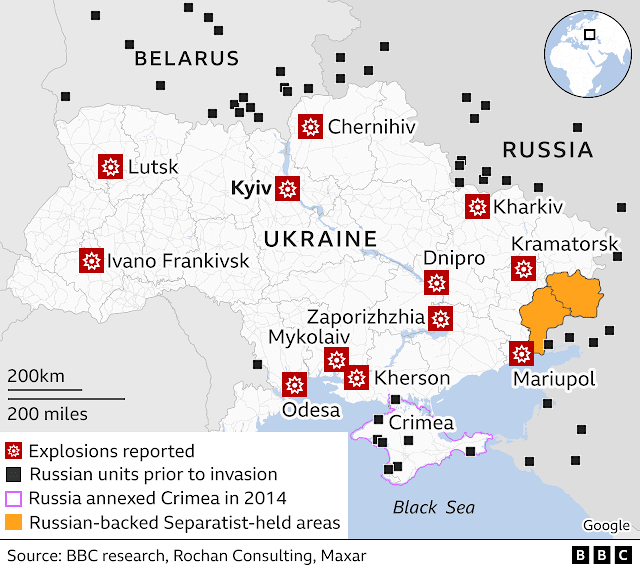

Recently, Ukraine has once again been hitting the headlines. This is in part due to the current energy crisis in Europe, as well as the build up of Russian military forces on its western border. Despite the Russian annexation of the Crimea in 2014, Moscow remains hugely involved in the affairs of Kiev, exerting significant pressure on its remaining territory. In these articles (split in to three parts), I will attempt to dissect why, despite it being thirty years since the downfall of the USSR, Russia remains so intrinsically involved in Ukraine and particularly, what role geography has to play in all of this.

The Problem With Ukraine's Human Geography

Ukraine’s human geography can be divided into two key points: the importance of Ukraine’s demographics and the sentimental attachment Russia attaches to Ukraine. To begin with the latter, both Russia and Ukraine originate from Kyivan Rus, while both share the Orthodox faith as their primary religion. Despite the split from Russia in 1991, these ties in the collective Russian mindset and to many Ukrainians (though not all, as resistance to the Russian presence in Donetsk and Luhansk has demonstrated) bind the countries to a degree much greater than mere neighbouring states. Indeed, the Moscow Patriarchate, Kiril II proclaimed on a visit to Moldova, that ‘spiritually we [Russia and Ukraine] remain one nation’ (however, since 2019, the Ukrainian Church has split from the Moscow Patriarchate).

Furthermore, when Russia annexed the Crimean Peninsula in 2014, Putin went so far as to justify the conquest in religious terms, stating that Crimea was ‘the place where Prince Vladmir was baptised. His…adopting [of] Orthodoxy predetermined the overall basis of the culture, civilization, and human values that unite the peoples of Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus.’ These factors feed into the broad belief among the Russian elites that Ukraine always has been and always will be an integral part of Russia. Ukraine is often identified as ‘little Russia’, an identification that leaves Ukraine devoid of its own psyche, subsuming it within Russia’s while attributing Russia a paternalistic role as ‘Great Russia’. This paternalistic role has historically been utilised as a justification for Russia’s interference in Ukrainian affairs. Indeed, General Denikin of the Russian White Army stated no Russian ‘will ever allow Ukraine to be torn away… [the] Muscovite Rus’ and Kyivan Rus’ is our internal quarrel, of no concern to anyone else, and it will be decided by ourselves.’

Interestingly, it was these writings of Denikin that Putin himself chose to reference in 2009 during a gas dispute with Ukraine, highlighting the continued perception among Russian elites that Russia and Ukraine are one of the same: two Rus’, a shared body and separate states in name only. Thus, as Russia militarily occupied an integral part of Ukrainian territory, Putin sought to illustrate this as a simple re-integration of a historical territory, while similarly seeking to highlight the religious similarities of the two nations.

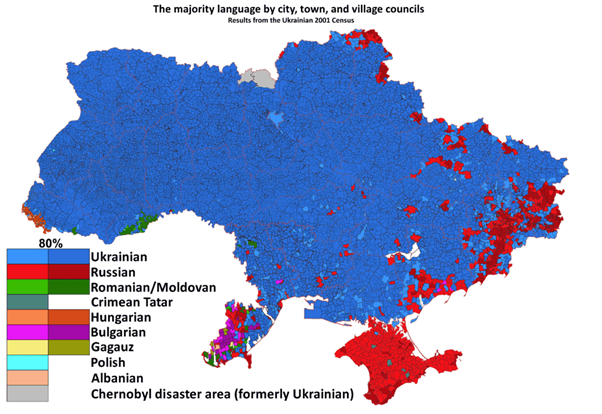

Yet religion, sentimentality and history are not the only facets of human geography that binds Russia to Ukraine. In a more tangible sense, Ukraine is a large Slavic nation, with significant volumes of Russian speakers (though it is prudent to note that many Russian speakers within Ukraine do not consider themselves part of Putin’s ‘Russkiy Mir’). Ukraine has a declining population, with a low birth rate and high levels of emigration, yet it is still a nation of over 41 million people, which includes 8 million ethnic Russians, or roughly 1/5 of the entire population. This number is already large, but to complicate the matter, there is an untold volume of Ukrainians who speak Russian and variably consider themselves as part of the wider Slavic or Russian family, as opposed to being solely Ukrainian. These groups are mainly located in the Crimean Peninsula, as well as in the eastern provinces of Donetsk and Luhansk. Russia has used this in the past as a pressure point to keep Ukraine in tow with Russian ambitions, but the removal in 2014 of the pro-Russian Ukrainian premiere Yanukovych, prompted the Russian invasion of the Crimea and support for insurgents in the Donbass region.

In his justification for Russian military intervention, Putin used protecting Russians as his casus belli, stating, ‘We proceed from only one thing, which is we cannot abandon the people who live in the southeast of the country… not only ethnic Russians but also Russian speakers who are looking towards Russia.’13 In no uncertain terms, Putin utilised Ukraine’s human geography to justify what was essentially an illegal intervention in a sovereign state’s internal affairs, plunging Ukraine’s eastern borderlands into a bloody and continuous conflict, while annexing the entirety of the Crimea. Thus, due to its demographics, Ukraine remains highly important to Russian geopolitics.

Comments

Post a Comment